Photo by Agê Barros on Unsplash

Managing Tech: Time

This is part of a series:

- Managing Tech: People

- Managing Tech: Heroes

- Managing Tech: Professionals

- Managing Tech: Time (you are here)

- Managing Tech: Cadence

If there is one skill I most commonly see underrepresented—among both individual contributors and managers alike - it is time management. As an individual contributor, weak time management makes it difficult to scale across the responsibilities that your business requires of you. As a manager, poor time management means you will represent neither your employer nor your employees particularly well.

In this post, I will review a range of time management approaches along a spectrum. You can compare these options, identify which best reflects your current approach, and explore alternatives. This post is intended for both individual contributors and managers.

Organization

The "why" of time management is straightforward: the more information you try to keep in your head, the less successful you will be at any one thing. The most basic approach to time management, then, is simply to get commitments out of your head.

This might be as simple as a paper calendar where you write down a task for a given day. If you prefer a digital workflow (as I do), you can use a calendar application and create an appointment for the day you intend to work on a task.

If you are going the digital route, I generally recommend placing the task at the time you usually start work or arrive at the office. That way, you are confronted with it immediately and can plan accordingly.

If you have multiple tasks scheduled for the same day, you can arrange them in an order that works for the project. This is basic prioritization, which I will return to later in the post.

Time Blocking

Once you are consistently putting tasks on your calendar, the next step is to account for how long those tasks will actually take - blocking off sections of time accordingly. Early on, you will almost certainly underestimate how long tasks take. Over time, you will develop better estimation skills.

A common misstep is forgetting to block time for tasks people take for granted: checking email, reviewing plans, or even eating lunch. I generally block the first 30 minutes of each day for email and planning.

It is easy to become overly precise and try to block time down to the minute. Instead, I suggest choosing a minimum block - 15 or 30 minutes - and sticking with it. Even if a task only takes 10 minutes, you might still allocate a 30-minute block. This gives you time to context switch and provides some buffer for unexpected changes.

Time blocking is useful not only for planning, but also for tracking past work. This can be invaluable during performance reviews when you need to recall what you’ve accomplished over the past year.

Eventually, you will find yourself with a fully blocked day - and then a new meeting request arrives. What now? This is where prioritization becomes essential.

Prioritization

...or learning to say “no.”

When a meeting request comes in for a day that’s already fully blocked, you need to decide what action to take. Which task takes priority?

My preferred approach comes from the Getting Things Done (GTD) system, which I’ve written about in another post. I will summarize it here for completeness:

- Do It: If you can complete the task now, do it.

- Defer It: You cannot do the task right now, so schedule time to do it later. Delegate It: If someone else can move the task forward, delegate it - and block time to follow up.

- Drop It: Some tasks do not actually need to be done. These are often informational and can be offloaded to another system (for example, a notes or knowledge base tool).

Learning to say "no" is a critical part of time management. Having a clear framework for prioritization makes this easier—and less personal.

A Word About Context Switching

For the individual contributor, meetings are often a distraction from deep work. Keeping email and corporate chat open throughout the day introduces constant interruptions. This is why I prefer to block time specifically for these systems and keep them closed otherwise. Context switching is expensive, cognitively speaking.

For the manager, meetings are your currency. Still, if you feel the urge to email or message a direct report, pause for a moment and consider the impact of that interruption. Is this truly the best time? Is it urgent?

I try to set clear expectations with my direct reports around response times. My general rule of thumb is that they can expect a response from me within 24 hours - and I expect the same from them. I make it explicit that I do not expect anyone to be "on" all the time.

As a manager, you also need to be mindful of how you communicate. A message with the subject line "Can we talk?" can trigger unnecessary anxiety. It can sound like a termination conversation when all you wanted to ask about next week’s vacation plans. Whenever possible, be explicit about your intent and provide guidance such as "not urgent" or "when you have time."

Likewise, talk with your team about preferred communication channels. Some people favor email; others prefer chat. Knowing how your direct reports prefer to communicate reduces the chance that important messages get lost - or ignored.

A Word About Systems

There are as many time management systems as there are stars in the night sky. I have not counted, but you get the idea. Over my 25 years in technology, I have studied and used many different systems. Below are a few that have stood out to me.

Patterns vs. Systems

The key is to avoid treating any single system as the final answer. Time management is a skill. A system - understood as an explanation of an approach - can help you develop that skill. The real value lies in understanding why the system is structured the way it is.

When a system is treated as the solution itself, it can box you into a rigid way of thinking and limit growth. Look for the patterns underneath.

Benjamin Franklin

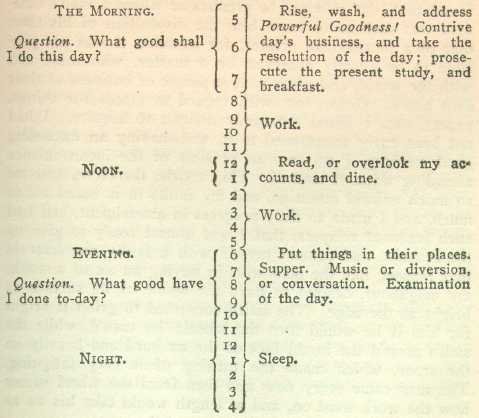

Benjamin Franklin used a daily schedule with a column of numbers down the center of the page: 5 through 12, then 1 through 12, and finally 1 through 4. This represented each hour of the day. On either side of the numbers, he recorded what he planned to do and what he actually did.

Franklin started his day at 5 a.m. and went to bed at a consistent time, allowing for seven hours of sleep.

That was his system. Does that mean you should start your day at 5 a.m.? Or sleep exactly seven hours? If you’re systematizing blindly, you might say yes. But the real lesson is the pattern: he started and ended his day consistently.

There are additional lessons in Franklin’s approach that are beyond the scope of this post, but well worth exploring.

Bullet Journal

For a long time, I preferred paper to digital. There was something satisfying about opening a notebook, uncapping a quality pen, and putting ink on the page. I still have notebooks from my time as a sales engineer (2000–2007), and I occasionally enjoy flipping through them to see what I was doing on this day years ago.

When I wanted more structure, I turned to the Bullet Journal system.

Getting Things Done

I have already referenced Getting Things Done. It is the system that resonated most strongly with me and the one that informs most of my current practices.

Franklin Covey

The original time management powerhouse, Franklin Covey once had physical stores in shopping malls where you could buy planners and stationery preconfigured for their system.

The key takeaway for me was simple: list the tasks you need to accomplish for the day. Cross off what you complete. Carry unfinished tasks forward to the next day.

What About Agile?

Agile approaches such as Scrum and Kanban are vast enough to warrant certifications. They are powerful tools, but in my experience, they are often overkill when mentoring or developing basic time management skills.

All you really need is a notebook or the calendar application that comes with your operating system. Anything more can distract from the core objective: building good habits. The best time management system is the one that works for you - whether that is a well-known framework or a custom blend of techniques.

I have had direct reports successfully use Agile systems for personal time management. That is fine if it works for them. However, it can become a blocker when everyone - including the company - is running a different interpretation of the same system.

Closing Thoughts

Time management is not something you "set up" once and then forget. It is a skill you practice, refine, and occasionally relearn as your role, responsibilities, and life change.

The mistake I see most often is treating a system as the solution. Systems are scaffolding. They help you learn the patterns - externalizing commitments, estimating time realistically, prioritizing intentionally, and protecting focus. Once you internalize those patterns, the specific tools matter far less.

For individual contributors, good time management creates space for deep work, learning, and sustained delivery. It reduces stress by making trade-offs explicit rather than implicit.

For managers, time management is leverage. How you manage your own time directly shapes how your team experiences work. Poor time management shows up as unnecessary interruptions, unclear priorities, and reactive leadership. Strong time management builds trust, predictability, and psychological safety.

You do not need a perfect system. You need an honest one - one that reflects how you actually work, not how you wish you worked. Start simple. Observe what breaks. Adjust. Repeat.

The goal is not to fill every minute of your day. The goal is to spend your time intentionally, on the work that actually matters.