Photo by CHUTTERSNAP on Unsplash

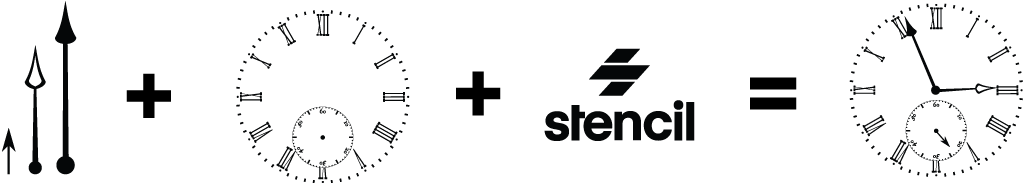

Building a Clock with Stencil

I have not seen a clock in a web-based user interface in a long time. This makes sense — they are pretty redundant these days. You have a clock on your watch, on your mobile device, and on your desktop, and those are just the digital versions available at a glance. Nonetheless, the process of building a clock can reveal a lot about how a platform works.

In this walkthrough we will take a look at building a clock component using Stencil. We will use SVG for the graphics, look at placement of the clock hands, and then review different ways to animate those hands.

The Template

SVG is useful for the graphics of a clock because they scale without losing quality. This is especially useful in a web component because you may not be sure about the size of the clock in the final display. You can also declaratively design the clock, rendering the necessary SVG as part of the template. You can take this as far as you need to get just the right look and feel.

In this example, we will use clock graphics that have already been designed using a vector editing program rather than attempt to draw every last piece declaratively.

The face of the clock is static — it does not change other than size/scale. For this, SVG gives us an image element. We tell the image element where to find the desired file, and it will be rendered to fit the corresponding placement.

The hands, on the other hand 🤪, will be rotated independently depending on the time of the day from the user’s machine. By placing the hands in their own SVG file and giving them an id we can reference them with the SVG use element. From there it is a matter of figuring out how far to rotate the elements to match the time of day.

render() {

return (

<svg>

<g transform={`

translate( ${this.width / 2} ${this.height / 2} )

scale( ${this.scale} )

`}>

<image

height="300"

href={getAssetPath( './assets/watch.svg' )}

width="300"

x="-150"

y="-150" />

<use

href={`${getAssetPath( './assets/hands.svg' )}#second`}

transform={`translate( 0 70 ) rotate( ${this.second} )`} />

<use

href={`${getAssetPath( './assets/hands.svg' )}#hour`}

transform={`rotate( ${this.hour} )`} />

<use

href={`${getAssetPath( './assets/hands.svg' )}#minute`}

transform={`rotate( ${this.minute} )`} />

</g>

</svg>

);

}All the clock parts — the face and the hands — have been grouped using an SVG g element. This allows us to transform the clock on the whole however we please without having to think too much about the coordinate system of the parts within the g element. In this case, that means scaling the clock to fit the available space, and positioning it in the center of that space.

For rotating the hands of the clock, we will leverage the transform attribute of the use element to specify a rotate() based on the time of day. We will get to the variables that determine the amount of rotation in a moment.

You can do these transforms in CSS as well, but you really need to pick one system and stick to it as the syntax is slightly different. For example, CSS will expect units such as

pxordegand also be more picky about comma separators, where SVG will not.

In this case, the rotation of the hands is less about style and more about functionality. For this reason, I will be using the SVG transform attribute directly in the markup. I find this also yields better readability for code maintenance.

The Placement

In order to know how to place the hands of the clock, we first need to know the time of day. A Date object will give us that information based on a 24-hour clock with sixty (60) minutes and sixty (60) seconds. While that is nice to have when working with time as we generally think of it, it makes for an odd bedfellow when doing tens-based math. For this reason, once we have a Date reference, we will determine the value as a decimal. For example, 10:30 becomes 10.50.

The next step then is to map 10.50 into the degrees of rotation. There are 360 degrees in a circle. SVG assumes degrees, not radians, in the transform and there are twelve hours on the clock (AM/PM is not displayed). Dividing 360 by twelve (12) gives us thirty (30) degrees rotation for each hour. In the case of 10.50, the hour is ten (10). Ten (10) multiplied by thirty (30) gives us 300 degrees.

For the minute hand, we are interested in the fractional part of 10.50 which is 0.50. Multiplying 360 by the fractional part of the decimal time of 0.50 gives us 180 degrees.

There are sixty (60) seconds in a minute. Using Date.getSeconds() will tell us the current seconds value. Dividing the current seconds by the sixty (60) seconds in a minute will give us a fractional value representing the percent of the number of seconds that have passed in the current minute. If thirty (30) seconds have passed, dividing by sixty (60) will give us 0.50, or 50%. We know that there are 360 degrees in a circle, and we want 50% of them to have passed. We multiply 360 by 0.50 and get 180 degrees.

componentWillRender() {

const today: Date = new Date();

const decimal: number =

today.getHours() +

( today.getMinutes() / 60 ) +

( today.getSeconds() / 3600 );

const hour: number = Math.floor( decimal );

const minute: number = ( decimal - hour ) % 1;

const second: number = today.getSeconds() / 60;

this.hour = ( 360 / 12 ) * decimal;

this.minute = 360 * minute;

this.second = 360 * second;

this.height = this.host.clientHeight;

this.width = this.host.clientWidth;

this.scale = Math.min( this.height, this.width ) / 300;

}

private height: number = 300;

private width: number = 300;

private scale: number = 1.0;

private hour: number = 0;

private minute: number = 0;

private second: number = 0;

@Element() host: HTMLElement;The scale and position of our clock will depend on the dimensions of the host element. For an exact fit within the host element, we look at which dimension is smaller, and divide it by the 300 pixels that represent the predetermined dimensions of the clock. You can think of this as having the effect of setting contain for background-size in CSS. However the host may be sized, the clock will always be within those bounds.

I have decided ahead of time that the diameter of the clock will be 300 pixels. This is reflected in the static SVG assets, and everything is sized accordingly. Once loaded into our component, we can choose to resize everything to fit as previously described.

All of these corresponding values for rotation, position, and scale are placed in component variables. When the render is performed, these values will be referenced, and the parts of our clock will fall into place accordingly. Now we have a clock that shows the current time... well, it did a second ago. Now the time on the clock is wrong. We need to update these values continuously which brings us to animation.

The Animation

When we talk about animation, we are talking about a loop occurring somewhere. Doing something like while( true ) in JavaScript is synchronous, and blocking, which is going to interfere with just about everything else happening in the browser. Fortunately, the browser figures this is coming and offers us a variety of options.

Among the choices is window.requestAnimationFrame(). Using window.requestAnimationFrame() we can create a loop that synchronizes with the refresh rate of the screen.

A call to window.requestAnimationFrame() is effectively asking the browser to let us know when it is going to render an update to the screen. To let us know about that update, window.requestAnimationFrame() takes a callback as an argument. In the callback you can make whatever adjustments you want, usually to the position of things in the DOM, or drawing state of a canvas element. At the end of the callback, if you want to continue the loop, you call window.requestAnimationFrame() again, passing the callback itself again. An animation loop is now established.

componentWillLoad() {

this.tick();

}

tick() {

const today: Date = new Date();

const decimal: number =

today.getHours() +

( today.getMinutes() / 60 ) +

( today.getSeconds() / 3600 );

const hour: number = Math.floor( decimal );

const minute: number = (decimal - hour ) % 1;

const millis: number = today.getMilliseconds() / 1000;

const second: number = ( today.getSeconds() + millis ) / 60;

this.hour = ( 360 / 12 ) * decimal;

this.minute = 360 * minute;

this.second = 360 * second;

requestAnimationFrame( this.tick.bind( this ) );

}

private height: number = 300;

private width: number = 300;

private scale: number = 1.0;

@State() hour: number = 0;

@State() minute: number = 0;

@State() second: number = 0;

@Element() host: HTMLElement;In order to kick off the loop, we can hook into componentWillLoad(). This method is called only once during the component lifecycle. In the window.requestAnimationFrame() callback, we do our rotation math as before, but include a milliseconds calculation. Capturing the milliseconds allows us to place the second hand between individual tick marks on the clock face.

Also now changed is that hour, minute, and second are all labeled as @State(). This means that when they change, the component render will be updated. All said and done, the process looks something like the following:

- The component loading process calls

componentWillLoad() - The

componentWillLoad()handler kicks off the animation loop by calling thetick()function - The animation loop determines the rotation of the hands and updates the component state

- Before exiting, the animation loop calls

window.requestionAnimationFrame()again, passing itself as the callback, thus ensuring the loop continues - The change in state causes an update to the component render

- The person viewing your clock now sees the updated time 👀🕰️

The Alternative

When following this flow, I was originally concerned that relying on state changes and diffing out the template changes would cause performance problems. To my surprise, the clock had no problem maintaining 60 frames/second (fps) rate on my laptop. Still, I had to be sure, so I wrote a slightly different version that circumvented state changes and went directly to the DOM elements themselves via references.

tick() {

if( this.clock_face ) {

const height = this.host.clientHeight;

const width = this.host.clientWidth;

const scale = Math.min( height, width ) / 300;

this.clock_face.setAttribute(

'transform',

`translate( ${width / 2} ${height / 2} ) scale( ${scale} )`

);

}

if( this.second_hand ) {

const today: Date = new Date();

const decimal: number =

today.getHours() +

( today.getMinutes() / 60 ) +

( today.getSeconds() / 3600 );

const hour: number = Math.floor( decimal );

const minute: number = (decimal - hour ) % 1;

const millis: number = today.getMilliseconds() / 1000;

const second: number = ( today.getSeconds() + millis ) / 60;

this.hour_hand.setAttribute( 'transform', `rotate( ${( 360 / 12 ) * decimal} )` );

this.minute_hand.setAttribute( 'transform', `rotate( ${360 * minute} )` );

this.second_hand.setAttribute( 'transform', `

translate( 0 70 )

rotate( ${360 * second} )

` );

}

requestAnimationFrame( this.tick.bind( this ) );

}

private clock_face: SVGElement;

private hour_hand: SVGElement;

private minute_hand: SVGElement;

private second_hand: SVGElement;Typically SVG element attributes are set using

setAttributeNS()but onlysetAttribute()seems to apply the changes from TypeScript.

Now, I am not particularly skilled in the art of performance testing, but I do know my way around. As far as I could tell, the performance was identical. The difference between whatever is happening to update the template based on state changes, and changes directly to the DOM itself, are so minimal as to be insignificant.

✋ But What About ...

Throughout this example, you may have noticed certain implementation choices that do not match those that you might have seen in similar examples. In any implementation there are such choices. Here are my thoughts on the choices I made, and why I made them.

CSS Animations

As far as I am concerned, CSS should be considered your first line of defense for most animations. Leveraging CSS allows the browser to tap into low-level features that we just do not have at the runtime layer (GPU, double-buffering, etc.). So why not use CSS animation in this example?

The only hand that moves fast enough to really need animation is the second hand. Each iteration in the animation loop would increment the rotation by six (6) degrees (360 degrees in a circle / 60 seconds/stops). At the first iteration then, we have six (6) degrees. Next is twelve (12) degrees. So on and so on until we get to 354 degrees.

.second {

transition: transform 1s linear;

}The next iteration will yield a rotation value of zero (0) degrees. When the CSS is updated, the transition will be applied. Setting rotation from 354 degrees to 0 degrees, means spending the next one (1) second moving counterclockwise back to zero. The transition does not look at the value as cumulative, or see that closing the distance is easier by moving clockwise.

You could create a variable that is cumulative. You could also remove the transition style, adjust the rotation of the hand, and then put the style back in place. For either approach, you now are writing code just to force a specific path, when both the state approach and reference approach deliver exactly what is desired in a performant manner that is easy to read and maintain.

In my experience, if you are writing code that feels like it is trying to bend the system to your will, then there is probably a better way to solve the problem.

setInterval() and setTimeout()

Despite having window.requestAnimationFrame() which was added specifically to synchronize animation with the refresh rate of the device, I see a lot of setInterval() or setTimeout() when developers talk about animation. The gap between these approaches used to be more significant. The main difference these days is that setTimeout() and setInterval() do not provide predictable intervals.

A call like setInterval( this.tick, 16 ) says that an interval of at least 16 milliseconds must pass before the callback is invoked. If the browser has more going on, however, it may defer the callback for however long it needs. This unreliability makes for a poor basis for any extensive animation.

Date.now()

You may have heard in the past that new Date() is slow relative to Date.now(). In this example, however, we are interested in the hours, minutes, and seconds of the day. A call to Date.now() gives you milliseconds since the epoch. To get hours, minutes, and seconds, you then have to perform extra math for the year, month, and day, subtracting them out along the way. With this math in consideration, the difference between new Date() and Date.now() is effectively nullified.

Next Steps

The post started by reviewing how to leverage and manipulate external SVG assets in our Stencil components. In early drafts of this example I built the clock face itself entirely declaratively, shape by shape. This gives you the ability to expose all fashion of styling, but trades complexity in both design workflow and maintainability. The balance is yours to find.

We also looked at turning hours, minutes, and seconds into decimal time, and then into degrees. Two different techniques for animating the clock hands were presented — one that relied on templating, and another that used element references, and we contemplated different implementation choices that might have been made.

Despite the display of the current time being available at a glance just about everywhere, should you ever need a clock component, you now know how to make one. Or if you prefer, check out the complete code for this example on GitHub. There is also a running example if you want to see the clock in action.